19th-century digital archives give black families a glimpse of their ancestors

After more than 20 years of researching her family’s origin in America, Nicka Sewell-Smith found the name of an uncle who had filed a complaint for stealing his horse. Another note stated that he had bought bacon, a broom, and tobacco at “Short’s Place” in Louisiana about seven months before the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865.

With his standard supply of popcorn and a drink at his fingertips, Sewell-Smith clicked on it and learned that Hugh Short was a black lawyer and slave owner. Then she came across Short’s will, which listed the names of his great-great-great-grandparents near the bottom of the document.

“I couldn’t turn away from the page for an hour,†she said. “I had resigned myself to the fact that I was never going to find them. So I called my cousin who had also been looking for 20 years and I said, “Guess what? We didn’t come here on a spacecraft from Cameroon and landed in northern Louisiana. ‘ “

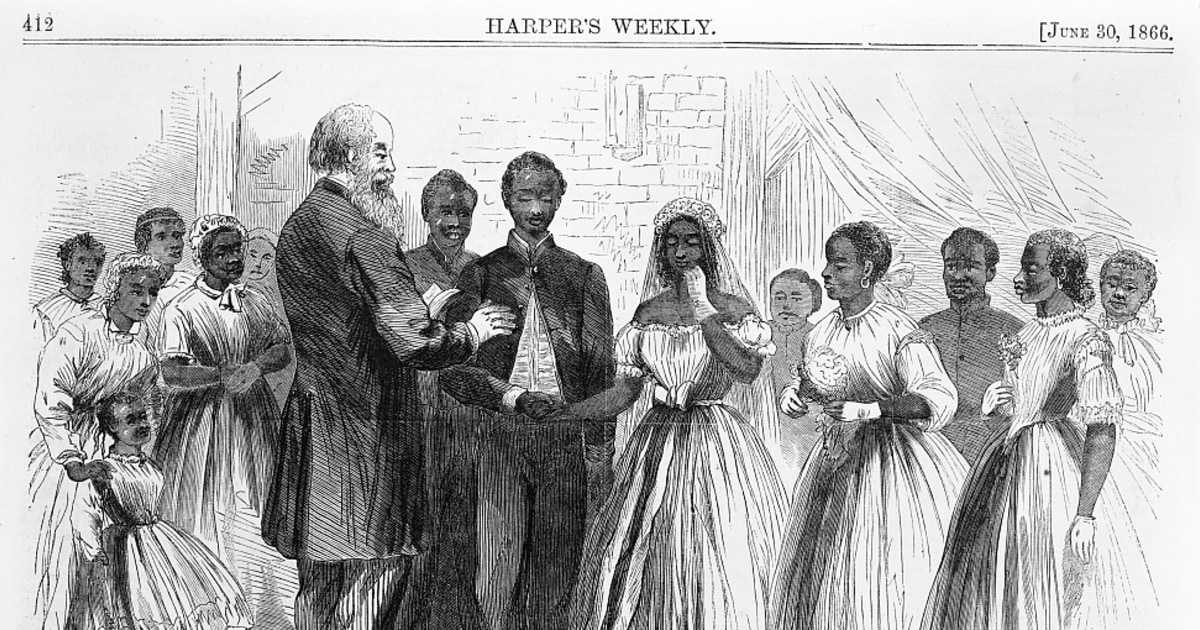

A renowned genealogist, Sewell-Smith gathered much of the information through the Freedmen’s Bureau, a formerly enslaved federal agency for blacks established towards the end of the Civil War in 1865. Its purpose was to help newly liberated people in their transition out of slavery. by negotiating employment contracts, legalizing marriages and locating lost relatives, among other things, documenting all of this. It has also provided food, shelter, education and medical care to more than four million people, including poor whites and war-displaced veterans.

For decades, information was hard to come by. It took patience and determination, attributes that enabled Sewell-Smith to hide in the National Archives, libraries, and research centers – and his home office – to peruse archaic microfilms by the thousands. , document by document.

However, this month, the genealogy site Ancestry.com unveiled a black family lineage game changer – 3.5 million records of previously enslaved blacks, available for free.

It is believed to be the world’s largest digitized and searchable collection of Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedman’s Bank archives. The collection delighted black genealogists and regular scholars alike, as descendants of slaves in America can learn more about their families in a much easier way.

“It’s very exciting and will help many scholars, historians and ordinary people to try to find out more about their ancestors,†said Angela Dodson, CEO of Editorsoncall, a company that provides editorial services to writers. Dodson has done extensive work on researching his own family tree.

“It is often very difficult for black Americans to trace their history because of the disruption of slavery, downstream selling, etc. She said. “I am often haunted by something I read in one of the accounts of former slaves who remembered black people wandering the roads and trails after the Civil War in search of long lost relatives. This post-war era is a crucial time to try to make some of these connections. “

Additionally, the collection is significant and game-changing as this is likely the first time newly released African Americans have appeared in records after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, as many enslaved people were previously excluded from the standard census. and federal documents.

“The enormity of this is that it’s something we knew to be there, but we thought it was beyond our fingers,†Sewell-Smith said. “To see ancestors commemorated… There are records in this collection where 100-year-olds were given rations in 1865. In the minds of most people, you can’t go that far back to black people. We count this automatically. – Oh, that’s not possible, not on paper. But it’s right there.

Dennis Richmond Jr., 26 from Yonkers, New York, found it amazing that at the age of 13, the iconic miniseries “Roots” moved him the way it did. He watched it with his father, who had used “every Sunday†to talk with his young son about his family’s lineage. As he grew older, the Freedmen’s Bureau became his daily focus.

“I come from two unique black families,†he said. “My father’s family was made up of almost free blacks, so they weren’t slaves. These were blacks who read and wrote, or bought and sold land, or sent their children to school.

“On my mother’s side of my mother’s family, originally from South Carolina, I found large plantations and sprawling fields and deeds of sale, and families buying from Africans on slave ships from Ghana, Mali and from Senegal. I discovered the Freedmen’s Bureau, thanks to my mother’s ancestors, because they were the ancestors who were enslaved during the Civil War.

These discoveries filled Richmond with pride, which he sees as the value for blacks to learn about their family history.

“We live in a time when so many people try to ignore certain stories,†he said. “But you can’t ignore history – when you can prove it. Especially when you’re connected to it. There’s the Freedmen’s Bureau, documents you can now access online that connects you to your story. I discovered that after slavery, my ancestor had saved money with other slaves for treatment. It almost made me cry. I would never learn that in public school. We knew we had carpal tunnel from all this cotton picking and asked for help. “

Linda Buggs-Simms of St. Louis is writing a book about her family after gathering information from the Mississippi State Archives and the Freedmen’s Bureau. She found a set of great-great-grandparents mentioned on an employment contract in Mississippi. She also confirmed the slave owner, who was the landowner on the contract, and discovered a photo of one of her new family members.

“There isn’t a day that I’m not on the computer looking for my family and reading other materials,†she said. “It’s addicting. See my ancestors registered on an employment contract … I tear up seeing their names. And now, with this breakthrough of the Freedmen’s Bureau, you can achieve records beyond 1870. It’s like tearing down the wall of Jericho.

Denessia Swanegan said she felt the same about accessing so much data. “As a little kid in the 1960s, I was always fascinated by the stories about family told by my parents and their siblings,†she said.

As an adult, she said, she began following her family’s history in 1980, “looking at reel after reel of census records on microfilm.” She found her great-great-grandfather’s name in the 1870 federal census and later – via a Facebook group called Our Black Ancestry – learned he was married on January 1, 1866 in Leavenworth, Kansas. , by Rev. Hiram R. Revels, who later became the first black person to serve in the United States Senate.

Additionally, she learned that her parent was among the first to volunteer to fight in the Civil War as part of the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry. Swanegan also found his death certificate and burial place.

“He didn’t have a gravestone,†she said, “so I was able to have a Civil War-era gravestone engraved with his name, rank and military unit with the “Veterans Administration set up at its resting place. This is one of the most satisfying achievements of my years of research.

It’s stories like these that make access to the Freedmen’s Bureau so important, she said.

“We have to be aware of the things our ancestors went through and how they persevered so that we are even here,†she said. “We’re doing them a huge disservice if we don’t learn about them and the lives they’ve led. We need to bring their stories to life and share them with future generations. Our future can only be improved by diving back into our deep past. “

Buggs-Simms added, “The greatest gift you can give your offspring is their heirlooms, so they can really know where they came from. With my two granddaughters, I am able to bring them back seven generations on one line and eight on another, and to have photos to support them. And it’s exhilarating.

To follow NBCBLK to Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.